First! I recently opened applications for my February Arizona Beginners Backpacking Trips- go from zero outdoors experience to knowing enough to plan your own backpacking trips! Plus eat KK’s incredible cooking. I imagine that these will sell out. Deets and the application are here, plus read reviews from past participants.

Also! Do you want to become confident with using caltopo for cross country navigation? And wander about in canyons in the beautiful southern Utah desert? There are still a few spots in my fall Utah trips, which are honestly a peak experience. Deets and the application are here.

Part two of this series is here, part three is here, part four is here.

Day one

June 14

I watch our plane, a wee Cessna 206 capable of carrying just four people and a small amount of cargo, roll across the ground on its tundra tires, pick up speed, and lift into the air. Behind me, the two Sarahs I’m on this trip with, who I’ll call SJ and SH, are rifling through our pile of gear. The plane just dropped us here, on this broad valley between high mountains in the western Brooks Range, an ungodly distance from the nearest road, and will pick us up in twelve days’ time, at another spot to the north.

“Where’s your second ursack of food?” asks SH, as she separates our things into piles.

“What?” I say distractedly, as I watch our plane become a tiny speck and then disappear.

“Didn’t you have two ursacks of food?”

“Oh,” I say, turning. The sun is positively blazing- the wee puffs of clouds here and there only seem to increase its intensity- and it’s lowkey hot. While this weather does happen in summer in the arctic, sort of randomly and when you least expect it, the current forecast calls for days and days of this heat and sun. It’s hard to believe- won’t it suddenly snow? Or at least some freezing drizzle? If it does stay sunny the whole time, this trip will be unlike anything I’ve experienced in the Brooks Range before. Be careful what you wish for, I say to myself, and then attempt to stop ruminating on the weather.

I survey the pile of gear scattered across the brown, lifeless-seeming tundra. Mid June is still spring in the Arctic and not a single thing has leafed out yet. Everything will burst voraciously into flower soon enough, and furiously work to complete its life cycle before the cold comes again in august, but for now the mountains have an otherworldly, barren look, absent of color and with patches of snow still clinging to the hillsides and in the narrow drainages.

My second ursack of food is, indeed, missing. And now that I’m looking, I realize my trekking poles are too. The ursack must’ve gotten left in the bottom of the plane, but the trekking poles are my own fault- I can picture them now, folded neatly in my suitcase of town things that I stashed at our bush pilot’s office in Kotzebue. I try to remember what was in that ursack- mostly just chips and extra toilet paper- it doesn’t seem like much, but the chips were to be a not insignificant amount of my calories out here, and since we’re out for twelve days I probably shouldn’t gamble with that. The trekking poles I could technically do without- I need them to set up my shelter but SJ has a two-person shelter we could share, and SH graciously offers to lend me one of her poles for hiking- but I still wish I had them. I text the pilot on my inreach. What luck! It turns out he’s returning in two days’ time to drop off a cache in this spot for another group, and he can drop my things then. Our plan had been to leave most of our food here while we do a three day loop to the south, and then pick up our food and spend eight days traversing to our exit point to the north, so this works out nicely. For three days I’ll share a tent with SJ and use SH’s pole, and then my missing things will magically appear just in time for our traverse.

I still feel like an idiot, though, as we bury the ursacks with our traverse food in a snowbank, hoping that will keep our bars from melting in the heat while we do our loop, and then hoist our not-that-heavy packs and set off across the flat, open land. I hope this dumb mistake was the only major mistake I’ll make on this trip, and is not a harbinger of things to come.

Almost immediately we stop walking.

“Which drainage are we starting with again?” I say, surveying the steep slopes of soft, grey scree to the south. We don’t have a finalized route for our trip- rather we drew a ton of options on the map and decided that we’d choose the route as we went- based on weather, our energy, and the vibes of the land itself, which was impossible to know before we arrived. Of the three of us, SH is the only one who’s spent time in this area- she loved it, and has been itching to come back and explore more. Much of our route will be new to her as well, and we didn’t know how the snow would be, or the brush. Now that we can see it with our actual eyeballs, the snow isn’t too bad, although it looks like it still covers the creeks in the narrower drainages, so we’ll be walking on it some. In addition to our route ideas, SH’s husband Luc added some things to our map that he saw on satellite imagery- “water features”, whatever that means, and a ridge that seems cool. SH has satellite imagery for all our options downloaded, and SJ and I have the slope-angle shading layer on caltopo- between the three of us, we should be able to make some excellent choices. And, as I stare at caltopo and then look up, comparing the map to what I see with my eyeballs, I realize that we have another thing going for us- these mountains are really, really walkable. Most of the passes go, the ridges are made of inviting white pixels, and there seems to be very little brush. The only thing limiting us will be our own energy. And all this sunshine? I just cannot.

We walk towards our first choice of drainage, a creek that cuts through a small canyon but seems to have walkable benches above it, according to slope-angle shading. I’m tired- I woke at 4 a.m. this morning to catch my flight in Fairbanks, which took me to Anchorage first, where I met the Sarahs, and then Kotzebue, an Iñupiaq village of about 3500 people on the western edge of the state. As the plane neared Kotzebue I was shocked to see that there was still a scrim of sea ice where the land met the sea- summer comes so late in the arctic, even if later it barrels forward at breakneck speed.

“Luc and I ice skated over that last winter,” said SH on the plane, pointing down at the glittering Kotzebue sound.

“You did what?” I said.

“The ice was really good,” said SH. Luc and SH are ice professionals, they basically have their PhDs in ice. Now the sound was open water, and its tiny waves glinted in the sun. I tried to imagine the sound in winter- flat, wind-scoured, smooth. Full of strange bubbles, elaborate cracks, and other icy phenomena.

In Kotzebue the two Sarahs and I exited the giant Alaska airlines jet, collected our luggage and headed across the street to our bush pilot’s office, where his tiny planes were parked. I’d brought a Ziploc bag of enchiladas and I ate them with a spoon as we repacked our things, enjoying my last taste of real food for a while. There’s so much adrenaline in getting ready for a big trip, getting items all in order and shuffling through airports at strange hours. Now, as we walk on the good crispy tundra under the hot sun in the late afternoon, I feel myself fading. The Sarahs are tired too- SJ was up until the wee hours last night, doing mushrooms at a beach bonfire in Anchorage, where the weather has been sunny for a few days and so the people have collectively lost their minds, and SH was up late packing. She had more packing to do than me and SJ- in twelve days, instead of flying out, Luc and another friend will be flying in with packrafts to meet her, and the three of them will spend two more weeks packrafting a river to the Arctic ocean.

I think about our flight in the tiny Cessna from Kotzebue to this spot- I had a queer sensation as we flew low over the soft, endless bog, pocked with clear shallow lakes, and then the high ridges rose up around us- it was a painful sensation, but not unwelcome- the almost violent feeling of being suddenly, and all at once, humbled. Look at me, with my fancy new-fangled gear, thinking I have a connection to this land. I don’t! I can’t make a sod house, or a skin boat, or even catch a whitefish. I’m like a visitor from space, wearing my special space-suit that creates a sort of rarefied air I’d die without. I can’t even fly a plane, or hunt from a snow machine. I live in a town big enough to have a Costco! I know nothing, am nothing.

We are neither as terrible or as important as we think we are.

We’re walking uphill now in the deep snow, and we’re postholing. I notice with a start that there are no mosquitos, not a single one.

“The idea is to thread the window between the snow melting and when the mosquitoes are born,” SH is saying, talking about why she likes to come out here in June. “Sometimes there’s a lot more snow, but if you hit it just right it’s great.”

Today is great. And, being weary, after four miles we decide to camp, on an almost perfectly flat tundra bluff, which is also great. There’s a creek nearby and I’m hot so I want to jump in, but the water is shockingly cold, so I just splash around a bit. SH is not dissuaded and she dunks her whole body, and will continue to do so every evening, no matter the water’s temp.

“Water can be colder than freezing and still not freeze, right?” I say to SJ as I watch SH swim, impressed. Just uphill is the creek’s headwaters- in a snowbank.

“Yeah a lot colder I think,” says SJ. “As long as it’s moving.”

I make my dinner, the instant refried bean and noodle soup I eat every night, on every trip, and add a few generous glugs of olive oil. I packed 33 oz of olive oil, in a plastic dr. pepper bottle. My goal is to eat some if it with every meal, to consume 3 oz/720 calories of olive oil a day, not counting the 12th day, when we’ll just be waiting for our plane. Olive oil is 240 cals/oz, more cals/oz than any other food, except other oils. So the more of it I carry, the lighter my food bag will be, for the same amount of calories. What I’m curious to see is if that much oil makes me sick to my stomach, or has other weird effects, or if I’m just… fine.

After dinner we tuck in, SJ and I in her spacious durston x-mid 2, and it’s so sunny, the sun just sort of circling above us like a bird of prey, that we have to close the vestibules for shade, which makes it really hot inside. I lay on my sleeping pad in just my underwear, my sleeping bag pushed to the side- my extra warm bag, that I packed anticipating normal, tempestuous arctic weather- ha! I pull my beanie down over my eyes and listen to one of Lian Moriarty’s funny, light-hearted chick-lit thrillers until I start to fall asleep.

Day two

June 15

Oh, to sleep eight hours on the quiet tundra and then wake and drink a cup of black tea in the bright sun- is there anything better in this world? If there is, I have not found it. My sleeping pad deflated twice in the night- it seems to have a new leak- but it didn’t drop me all the way to the ground and the tundra is soft anyway, so. As we eat breakfast (glug glug goes the olive oil into my granola, and it actually tastes pretty good) we look at our maps, deciding where we’ll go today. Doing a loop is really fun it turns out? Because you can make it as long or short as you want. The pressure is off! We choose a ridge, and on the climb up there are eleventy billion caribou trails- almost as if someone has drawn a giant rake across the land- but no actual caribou or caribou sheds to be seen.

We’ll learn from our pilot later, when we pepper him with questions after the trip, that the caribou are still on the flats north of here, having their babies, that they haven’t yet been driven into these mountains by the bugs. And that they always shed their antlers on the same part of their yearly cycle, and when that time comes they’ll be far to the east. Sometime after we’re gone they’ll appear where we are now- the Western Arctic caribou herd, once numbering half a million but now down to 140,000, flowing across the land like a plague of locusts, cutting deep grooves into its surface. No-one knows exactly why this herd is in decline, but with climate change willows, alders and dwarf birch are growing in much larger areas than before, slowly brush-ifying the tundra, and people think this makes it harder for the caribou to travel.

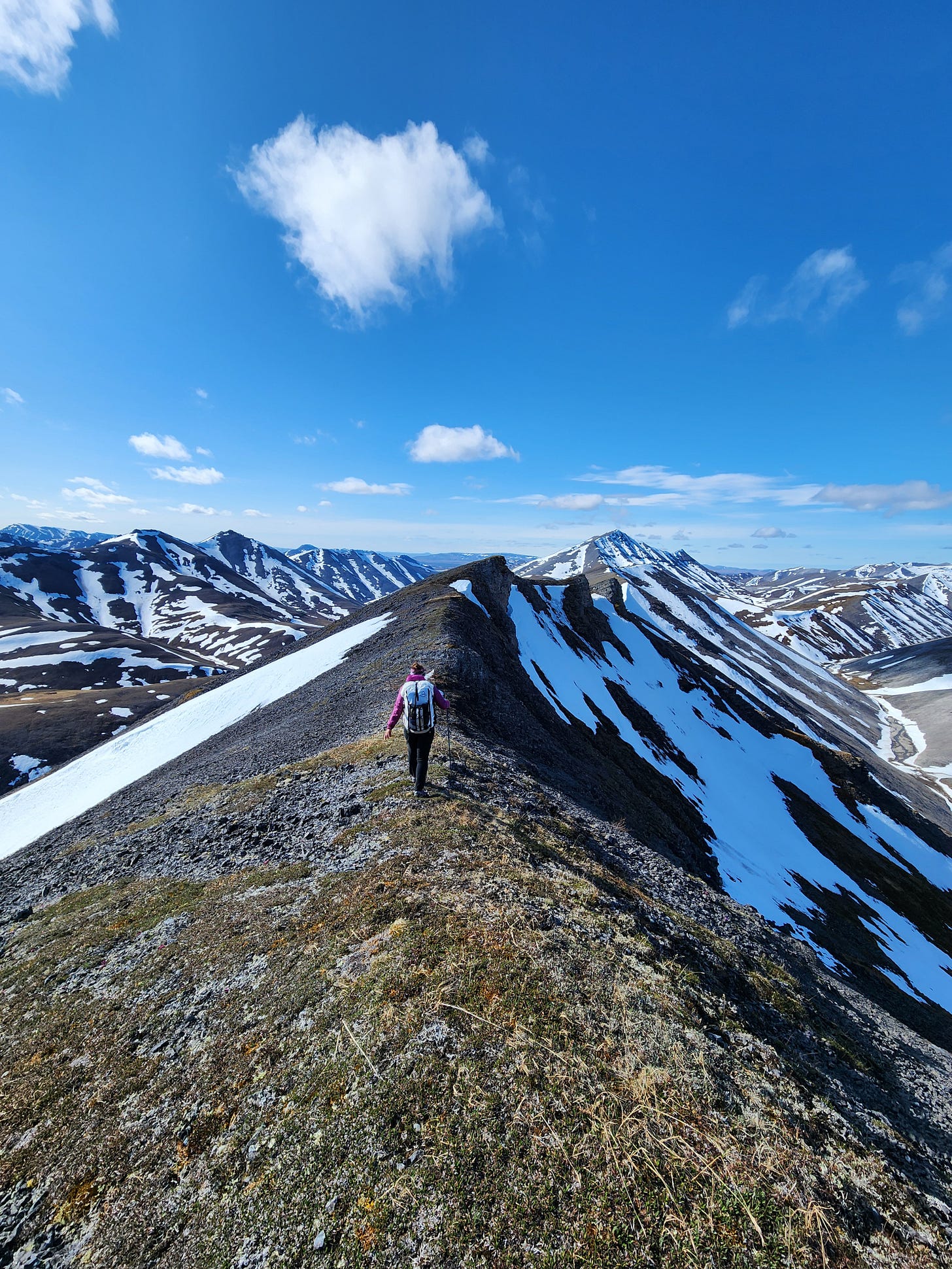

The ridge we walk is amazing and there’s a hawk above us, circling, which is remarkable because so far we haven’t heard or seen a single bird. Maybe because the mosquitoes aren’t born yet? When the mosquitoes appear, will the birds appear too? From this vantage point we can see the land in all directions and we pull out our maps and use this new info to plot our next moves.

We decide to find Luc’s “water features”, even though SH says he’ll be lowkey sad we looked at them without him. They turn out to be the most beautiful waterfalls! One after the other, turquoise water that cuts its way through some sort of dark, layered rock that none of us know. In fact, none of us know anything about rocks at all. We discover that we have all attempted, somewhat half-heartedly, to learn rock things, and then forgot. I propose the idea that rocks are actually unknowable. Henceforth, when we come upon a cool rock thing, we’ll wonder about it and I’ll say “Too bad rocks are unknowable,” and the others will say “Yeah, a total mystery.”

After blazing all night, the sun decides to once again blaze all day. My face is roasted already, and I contemplate if, at the advanced age of 42, I should become the kind of person who actually reapplies my sunscreen. If you read the bottle, you’re supposed to do it every two hours. If I’m out in the sun for fourteen hours, does that mean I should reapply seven times? That seems insane. I’m definitely not doing that. I run this idea by the others.

“Don’t they say that between ten a.m. and two p.m. is when the sun does the most damage?” says SJ. “So really sunscreen is most important then?”

“Except out here it’s more like between two a.m. and ten p.m.,” I say. “So we’re screwed.”

In the evening when we get to camp the sun has dropped into its most sadistic position- low enough to get under the rim of your hat. I want to crawl into a dark hole and hide, but there are no dark holes anywhere. In fact here in the land north of treeline there isn’t any shade at all. There is, however, an icy creek, and we do what will become our nightly routine- taking off our clothes and splashing in the water and then walking around naked, cool for a few blessed moments. I’m tired but my body only hurts medium- we’re hiking around 8-10 miles a day, which is enough up here to make you feel like you did something, but not so much that you’re wrecked. We’re on another flat tundra bank- nature’s perfect upholstery- next to another cute burbling creek, and I am grateful to retreat into to silnylon of SJ’s shelter after dinner, and listen to about a minute of my audiobook before falling asleep.

I tapped every single photo so I could scroll in and see all the details

Wow! Great pics! I used to take students out on field trips… when asked what” kind of rock is this?” I’d say “FDRDK” which meant funny damn rock, don’t know.